April 18th 2025

Mishel Tachet

tachetmishel@berkeley.eduMishel Tachet is a first-generation university student, completing her undergraduate degree in Anthropology. Her focus is on cultural and environmental anthropology, interested in multi-species ethnography, natureculture themes, climate change, and borders and immigration.

Upon acceptance to the Off the Beaten Track Fieldschool located in Gozo, Malta, I was faced with the daunting task of traveling across the world alone. My research paid close attention to placemaking through sensorially recognizable pathways, and in doing so, I noticed the ways I made sense of this new environment. In many ways, Gozo was quite similar to my home state of California. The small island provided a familiar view of the sea, the hot summer created parched hillsides with various brushes, and the towering nopales (cacti) reminded me of home. The field school provided an activity in which we were tasked with making a meal that shared an aspect of our culture with the other participants. I shopped the local grocers, searching for ingredients to share my Mexican heritage with my peers. This proved quite difficult, as staples I was used to, such as pinto beans, corn tortillas, and dried chiles were not accessible here. It forced me to find alternatives, such as using a brown Italian bean that had a mild flavour, making my own flour tortillas, and harvesting from the plentiful nopales outside. In a small kitchen in the central Mediterranean, I enacted a kind of ritual, one that had been practiced every morning by family members before me.

Scrape. Cut. Boil. Grill.

Knead. Shape and Pat. Press on the Comal.

And like all the great women before me – flip the tortillas with your hands.

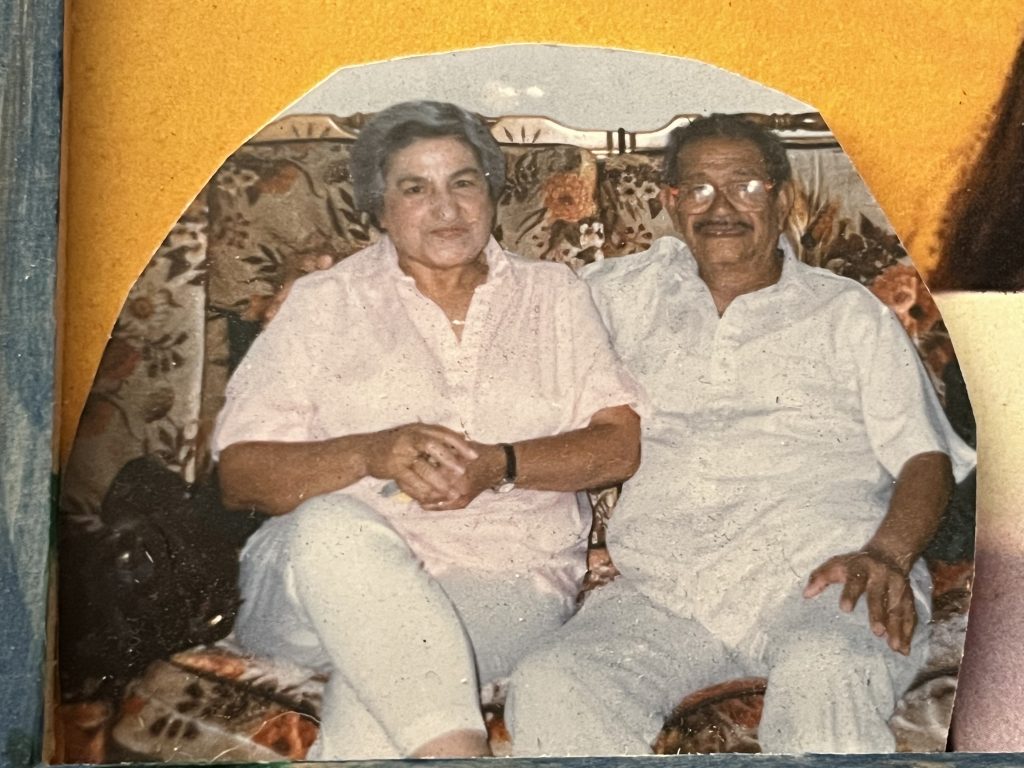

As I shaped the masa and prepared the cactus, I thought of my great-grandmother, who would make tortillas from scratch every morning for her eight children before she went to work the fields. The movements I was enacting then were the same she once did. Like the nopales that grow feverishly along the Goiztan hills, I am not from here. The cactus was introduced from Mexico in the 16th century and quickly became a beloved plant. Today, the sight of the broad green structures and their red fruits are active placemakers for Gozitans, who look to the prickly pears’ blooms as a staple of home and as a way to situate the seasons. The nopal is hearty and resilient, with the unique ability to withstand intense heat and sunshine while retaining water within its prickly shield.

In the wake of intense anti-immigrant and xenophobic rhetoric in the United States that paints Mexicans and Latines as criminals and attempts to stifle immigration, we can look to the nopal as a symbol. While Gloria Anzaldua (1987) utilizes the native workings of corn as a way to point to the resilience of the Mexican people, I find the nopal is another more-than-human that we can look to. The nopal is beloved in Gozo, despite its immigrant status, and thrives in this tiny island thousands of miles from its native homeland. Borders attempt to construct stagnant perceptions of people, place, and nonhumans, but nopales remind us that migration is fluid and beautiful. I had not expected to find myself among the foreign hills of Gozo, and yet, to my surprise, I felt closer to home and my heritage after my time on the island. When I look at the Gozitan hillsides, I see the terraced walls, the drying brushes, and the green nopals. In the spiked leaves, I see my mother cooking in the mornings, I picture my grandmother and her hardworking hands, I see the ability to withstand and continue: I see resilience.

Sources:

Anzaldua, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontura: The New Mestiza.